What's needed for AI agents to work

Trends in data access, AI primitives, data infrastructure and the scaling of best practices all suggest useful AI agents will rapidly scale in the next ~decade

Written on

I'm willing to bet a lot of money that AI agents will work over the next decade.

Today's AI agents are where self-driving cars were 10 years ago. In 2015, self-driving cars could navigate a closed course flawlessly but would panic at an unexpected construction zone. Today's AI agents can write elegant code but stumble when asked "should we include this graph in the client deck?"

We're in the same transitional moment--and the path forward looks remarkably similar. Over the next few years we will start to see agents excel at an increasingly wide variety of tasks, and this will lead to drastic changes in our work and in our lives.

To understand why, we first need to examine how rapidly the underlying language models have advanced.

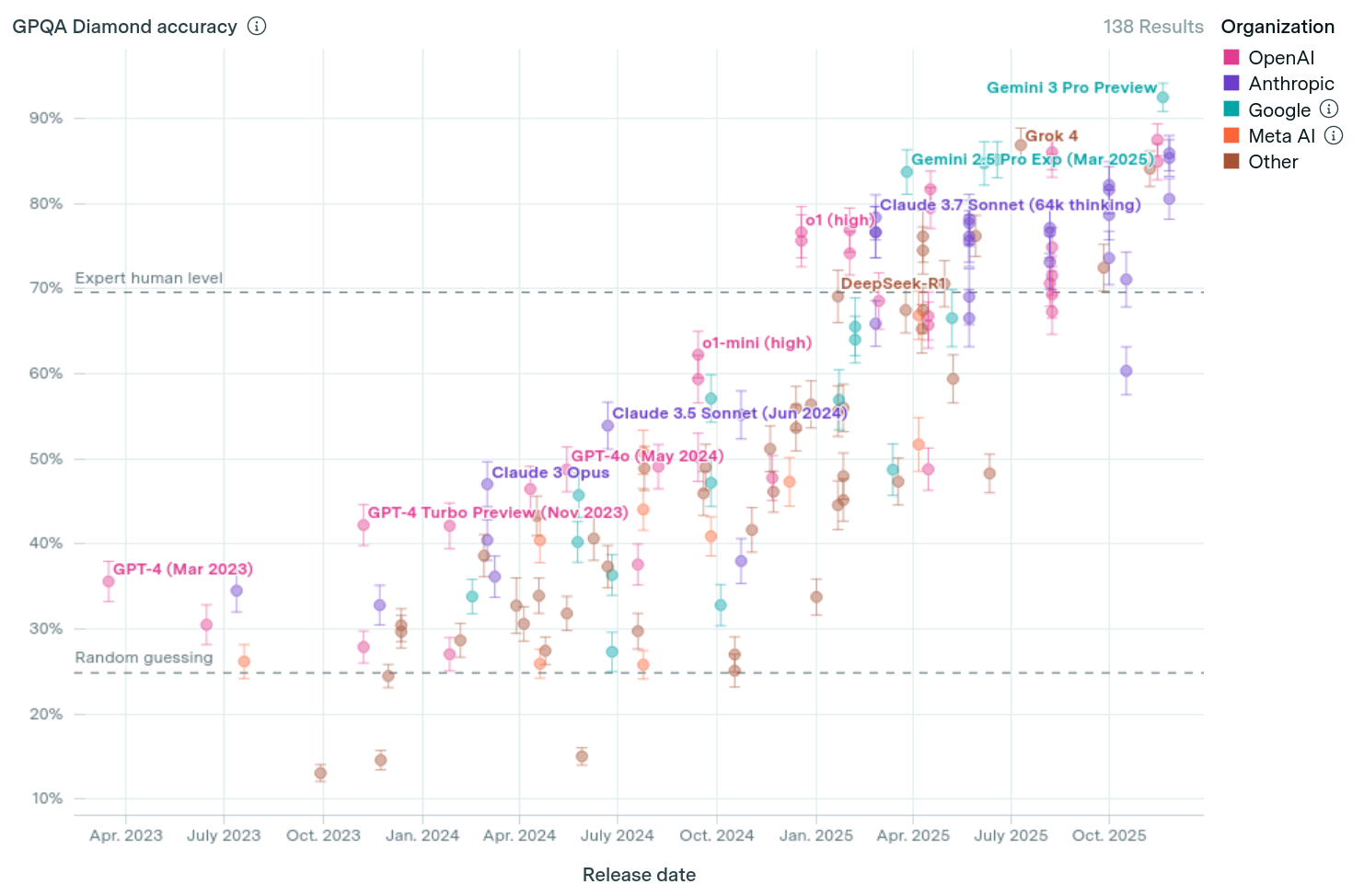

Below is a real example question from GPQA, a challenging dataset where human graduate students achieve ~70% accuracy. Today's best models are ~90% accurate:

Astronomers are studying a star with a 1.5 solar radius and 1.1 solar masses. When the star's surface is not covered by dark spots, its Teff is 6000K. However, when 40% of its surface is covered by spots, the overall photospheric effective temperature decreases to 5500K. In the stellar photosphere, when examining the ratio of the number of neutral atoms of Ti in two energetic levels (level 1 and level 2), astronomers have observed that this ratio decreases when the star has spots. What is the factor by which this ratio changes when the star does not have spots compared to when it has spots? Note that the transition between the energy levels under consideration corresponds to a wavelength of approximately 1448 Å. Assume that the stellar photosphere is in LTE.

A. ~2.9

B. ~1.1

C. ~4.5

D. ~7.8

I don't even know what that question is asking, and would have no idea where to get started, but we're at the point where models have far surpassed even graduate students with experience in the relevant field. And this progress has happened over just the past few years:

Sure, some of these model providers may have over-optimized their systems for these tasks, or overfit to the training (or even the test) data. But the trend on all of the other challenging datasets looks the same; absolute performance is similarly impressive; and at least the leading providers (like OpenAI and Anthropic) are very serious about their evaluations, as can be seen by how well their previous systems generalized on held out problems

If AI models can answer these difficult questions with a high accuracy, it seems like we really should be able to make models answer questions like "Should I email the customer about this?" and "Should we include this graph in the powerpoint presentation for client?"

Which is precisely what is needed for AI agents to actually work.

How language model capabilities enable AI agents

Language models answering graduate-level multiple choice questions are sort of like the self-driving cars of 2015 being able to outperform a human driver on a closed race track--impressive, but ultimately not that useful. And the delta between "great performance in a closed environment" and "actually useful in the real world" is caused by the same underlying factors that caused that disconnect for self-driving cars back then.

Ultimately, all knowledge work boils down to a series of decisions--questions of the form "what is the best thing to do next?" In theory, having large language models that are good at answering questions ought to enable powerful AI agents.

But today, AI agents don't really "work"--they're interesting and fairly useful in some small domains (like computer programming), but the vast majority of knowledge work is still done by people.

So why the disconnect?

The four missing pieces required for agents to "work"

I argue below that the disconnect is not fundamental (as some skeptics argue1), but rather that there are four practical missing pieces required before we see AI agents actually "work":

- Exposing data to agentic AI systems

- Codifying best practices

- Developing new AI primitives

- Building infrastructure to support large scale inference

These missing pieces are precisely the factors that enabled self-driving to work, and we will see significant progress for AI agents on each of these axes in the near future.

Each of these activities is being aggressively pursued by a wide range of companies, organizations, and people, and I believe we should expect to continue to see rapid improvement in each over at least the next few years. And if we make progress on each, AI agents seem likely to work far better than they do today.

1. Exposing data to agentic systems

In order to make self-driving cars really work, the cars needed to move from "car with cameras" to "car that knows every curb height and lane marking in its operating area." The breakthrough was less about better algorithms for control, and more about giving cars access to a richer understanding of their environments via access to more data (including HD mapping and sensor fusion), as well as much better understanding of that data.

A large part of why humans are still so much better than AI agents at many knowledge work tasks is simply that we have access to more data. We can answer the question "Should I send this to the client" not because we are fundamentally more clever, but because we've interacted with the client in person, we've gone back and forth in Slack messages with our colleagues, and we've overheard snippets of relevant in-person conversations and context. Many of the questions are not hard to answer when given access to the right information--it's just that all of that information is scattered throughout space and time and a thousand different internal and external systems.

If AI agents are to actually work well enough to make a meaningful impact on the world's economy, they will need access to the same data as their human business-person counterparts.

AI agents currently lack easy ways to acquire that data, but as more of that data becomes digital even the performance of today's systems might be sufficient for a fairly large set of the business-relevant tasks we do today.

Because of this, tons of people and companies are working aggressively on solving this problem. OpenAI, Anthropic, and Microsoft all have integrations with popular data sources (ex: Google Drive, your email, Notion, etc) in order to give their systems access to your business and personal data. Microsoft Copilot is built into the Windows operating system specifically because it can (at least in theory) have more access to data. Startups like Glean and others are scrambling to make internal corporate data searchable and more accessible to agents, and the whole reason for all of these RAG (retrieval augmented generation) startups and infrastructure libraries is that such techniques hold the promise of making more data accessible to AI.

Coding agents like Antigravity and Claude Code are being created by the big players not only because they're a good business, but because coding agents are yet another way of conveniently making more data accessible to future AI agents (e.g. by enabling the agent to write ad-hoc integrations and data access scripts itself)

While much of our data is scattered and hard to access now, I'm quite certain it will be a very different story in 10 years.

2. Codifying best practices

AI is improving incredibly quickly. The products you see today were developed on earlier models, and have not yet incorporated any of the research published within the past 6-12 months. There are virtually no best practices and no real body of knowledge for how best to design practical agentic systems.

It feels like almost every day that there are new, genuinely useful new techniques being developed by advanced users of coding agents. More complex earlier ideas (like MCP servers) are being replaced by simpler primitives that are easier to use (ex: see Anthropic's recent "Agent Skills" in Claude Code).

It takes both time, and real world experience (and failures) in order to develop these best practices. Much like in self-driving, where the successful companies realized early that simulation alone was insufficient; you needed millions of real-world miles to encounter the long tail of edge cases. Agents face the same challenge: we're still in the "accumulating miles" phase, figuring out which techniques work in which contexts. Every failed agent deployment is data. The best practices will emerge from deployment, not theory.

The process of creating best practices is fundamentally about discovering these real-world failure cases--and finding ways to increase reliability by preventing similar mistakes in the future. Today's language models have been optimized to do a "good enough" job for consumer use cases without driving the cost up too much. But as companies shift to agents doing real work, there will be increasing demand for accuracy and reliability, even if the cost ends up being higher.

And there already are a variety of fairly simple ways to increase model accuracy by simply paying more--it's just a matter of figuring out best practices about which techniques to apply when. For example, "ensembling" is a well-known technique in the traditional machine learning literature which allows one to incur higher costs in order to get better accuracy (basically, an "ensemble" of different models all answer the same question in order to have their errors "cancel out"). In fact, with questions where the answer can be objectively and deterministically evaluated, it's possible to simply sample even a single model multiple times--recent research has shown that doing so will continually increase the chance of finding the correct answer. As more samples are drawn, the chance of finding the right answer increases log-linearly with the number of samples, which is actually pretty good!

We've seen these techniques perform well in our own work as well: by using multiple models, by taking multiple samples, and by allowing AI agents more time to think and use tools, we've seen much better performance on a variety of tasks (everything from generating code to identifying bugs in existing code). Our product, Sculptor, takes advantage of these types of techniques in order to identify potential problems for users, and we're working on adding a native "sampling" mode to make it even easier to try out multiple coding agent models simultaneously on the same problem.

Over the next few years, we should expect to see far better performance in AI agents--even if the underlying models and capabilities remain exactly the same (which seems unlikely).

3. Developing new AI primitives

Self-driving benefitted massively from the creation of new AI models like "transformers"--the models that also power today's language models and agents. First released in 2017, transformers enabled self-supervised learning about the visual world in a way that was extremely useful for self-driving cars. Originally just one small component in a larger, more traditionally engineered system, these and other new AI models have grown in scope and complexity to the point where today's self-driving software stack is largely new AI models that are trained "end-to-end".

Part of the reason why we should expect AI agents to work more broadly is that the underlying models and AI tools will continue to improve. Companies will continue scaling up their models, refining their data and techniques, and devising cleverer ways to set up the training methods for their systems.

But it's important to realize that AI research is not slowing down--if anything, it's accelerating.

The number of papers submitted to NeurIPS (the largest AI conference) each year has grown by over 10x over the past 10 years2--and there has been little (if any) drop in quality. Each year, we get new papers for more efficient models, distributed training, new types of memory, and other transformative new techniques that enable yet more powerful AI systems.

We're even starting to see the beginnings of fundamental scientific laws for "deep learning" (the technology that underlies modern AI, and which is still more black art than repeatable science and engineering). Such theoretical breakthroughs could, in the best case, enable far more efficient methods for training models (and in the worst case, would at least allow us to understand the natural limits of our current approaches).

These coming breakthroughs--both the theoretical, as well as the practical--will help dissolve the current barriers to AI agents actually working. Even if the skeptics are completely right, and the current paradigms are insufficient for "true" intelligence (whatever that means), such claims are unlikely to be true forever: new graduate students and researchers will be continuing to build on top of earlier work, and invent new ways of thinking about AI that could allow us to break through those limits.

In a sense, that's already what we have today--today's systems are not some simple, single algorithm, but a collection of tools, tricks, and hacks that we have collectively refined over the past few decades of research. Adding more tools to the toolbox will simply make it easier to make even more intelligent systems.

It's hard to predict the exact order in which various breakthroughs will appear, but it's a pretty safe bet that they will appear. There's simply too much money and talent flowing into the space for any other outcome to be particularly likely.

4. Building infrastructure to support large scale inference

One of the most under-appreciated reasons why self-driving cars work today is all of the infrastructure that was created behind-the-scenes. Waymo isn't just a self-driving car--it's a whole stack of fleet management infrastructure, maintenance operations warehouses, an app with geofenced deployment rollout, and even remote assistance for challenging situations. Both Waymo and Tesla invested heavily in infrastructure for data collection, model training, and simulation--literally thousands of people have invested years of their lives in these critical infrastructural tools, and it is this effort that is what has really enabled self-driving to work.

Similarly, much of what is stopping agents today is purely infrastructural: the necessary software and hardware is still in its infancy.

On the software side, besides infrastructure for accessing data (mentioned above), agents need a wide variety of boring, standard support for creating, debugging, monitoring, and deploying agents at scale. While it's easy to run a single agent, it's much more difficult to run millions of them in a way that is secure, repeatable, monitorable, and allows us to evaluate their performance. There are hundreds of new startups and software libraries popping up to deal with these challenges, and while many of them have grown incredibly quickly over the past year, there's still a lot left to build before AI agents are painless to create and deploy.

On the hardware side, the new infrastructure requirements are even larger. Multiple companies are each pouring more than $100B into AI data centers precisely because they are betting (in a huge way) that AI agents are going to really take off. It's a classic example of Jevon's Paradox, where increased efficiency can actually lead to increased demand: as the models get cheaper, the demand has skyrocketed. For example, OpenAI just released a report showing that usage of "reasoning tokens" has increased by 320x in the past year.

These sorts of infrastructural bets create a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy: if Microsoft and Google are wrong about the future demand for AI inference, and over-build datacenters, then the cost for using the resulting computer hardware will plummet, which will make it even more attractive to build AI agents to take advantage of that cheap compute. It seems very unwise to bet against a technology working when companies are pouring literally $100B+ into it (and into the supporting infrastructure)--even if they're wrong about the timing and lose a lot of money, they will create an abundance of cheap inference that will enable future AI agents.

Even once agents "work", deployment will take time

Even after the above barriers to useful AI agents are largely surpassed, and we have the ability to create extremely useful AI agents, the world will not be transformed overnight: there are plenty of barriers to adoption beyond just the difficulty of creating a working AI agent. Just as self-driving cars work today in sunny California (but not necessarily in a NY blizzard), there will necessarily be a slow expansion as capabilities improve.

But even if deployment of AI agents takes another decade, we're still talking about a radical transformation happening over a fairly short (~20 year) time scale. A world with reliable, functional AI agents that can outperform humans at most (if not all) knowledge work will likely be quite different from the one in which we live today.

It's worth recognizing just how much easier the problem of AI agents is relative to self-driving cars. Waymo has a much more difficult problem: it's controlling two tons of steel traveling at extremely high speed right next to other humans. Any mistake could be a matter of life and death, yet Waymo has managed to produce cars that have driven millions of miles at this point, and without causing a single fatal accident. There's no "undo" when you're driving; there's no ability to "pause" or "wait for the human to come check things out when you get confused". In contrast, using AI agents for knowledge work is a vastly easier problem.

Today's AI agents are where self-driving cars were 10 years ago. The DARPA grand challenge for self-driving had been won back in 2005, but in 2015 it still felt like we weren't really any closer to full self-driving in practice. Since then, billions of dollars of investment have taken us from cars that can barely manage to stay within a lane to a fully automated taxi service that can take you anywhere in the San Francisco Peninsula. It's amazing what a few billion dollars and thousands of smart people can do over a decade.

Much like self-driving over the past decade, today AI agents are poised to transition from something that works in "theory" to something that works "in practice".

Bit by bit, our tooling is improving, allowing us to make ever more powerful systems. It's not the "recursive self improvement" / "hard take-off" scenarios of AI doomer nightmares, but rather the inexorable advance of technology and capitalism--ever better, ever faster, every more efficient systems for developing, optimizing, understanding, and running what is ultimately just various types of software. The fact that that software happens to be taking in every internal conversation at your company, or that it is now outputting think pieces and creating marketing content, doesn't change the fact that it is just software. It's just that it's getting much easier to make much more useful software.

In a sense, it's this "incrementalism" that is the strongest argument for why agents will ultimately work: as long as the world continues operating roughly as it does today, software never gets worse. Today's agents are the worst agents that will ever exist--AI agents can only improve over time3, and are doing so at an incredible rate. Agents are already incredibly useful in limited domains today (ex: certain coding tasks, finding security vulnerabilities, testing, summarizing, etc), and the set of tasks at which they excel can only really expand over time.

So whether it's this decade, or the next, I'm confident that we'll have useful AI agents in the near future.

Given that, now is probably a good time for us to start asking what that means for our jobs, our communities, and our future--which will be the topic of my next post!

- There used to be a significant contingent of respectable AI researchers and scientists who believed that modern AI systems were missing fundamental pieces of what makes up human intelligence. Today, those numbers have dwindled to the point that practically no one believes that AI systems are fundamentally incapable of doing most cognitive work, but rather the disagreement now is more about precisely how much engineering work is left. This is evident in how experts have been repeatedly revising their estimates of "when will we get really powerful general AI systems" to be much shorter over the past decade or so, and we now have above-average performance even on the benchmarks that were explicitly created to demonstrate how much better humans are than AI systems ↩︎

- NeurIPS 2015 had 1,818 submissions, and there were 21,575 submissions in 2025 ↩︎

- Because AI agents are software, any new version of that software that is worse can generally be "rolled back" to an earlier version that was better. This ability to roll back is not always accessible to end users (for example, you cannot use earlier models from OpenAI if they've been removed), but with open agents, this is always possible (which is another good reason to prefer open agents). ↩︎