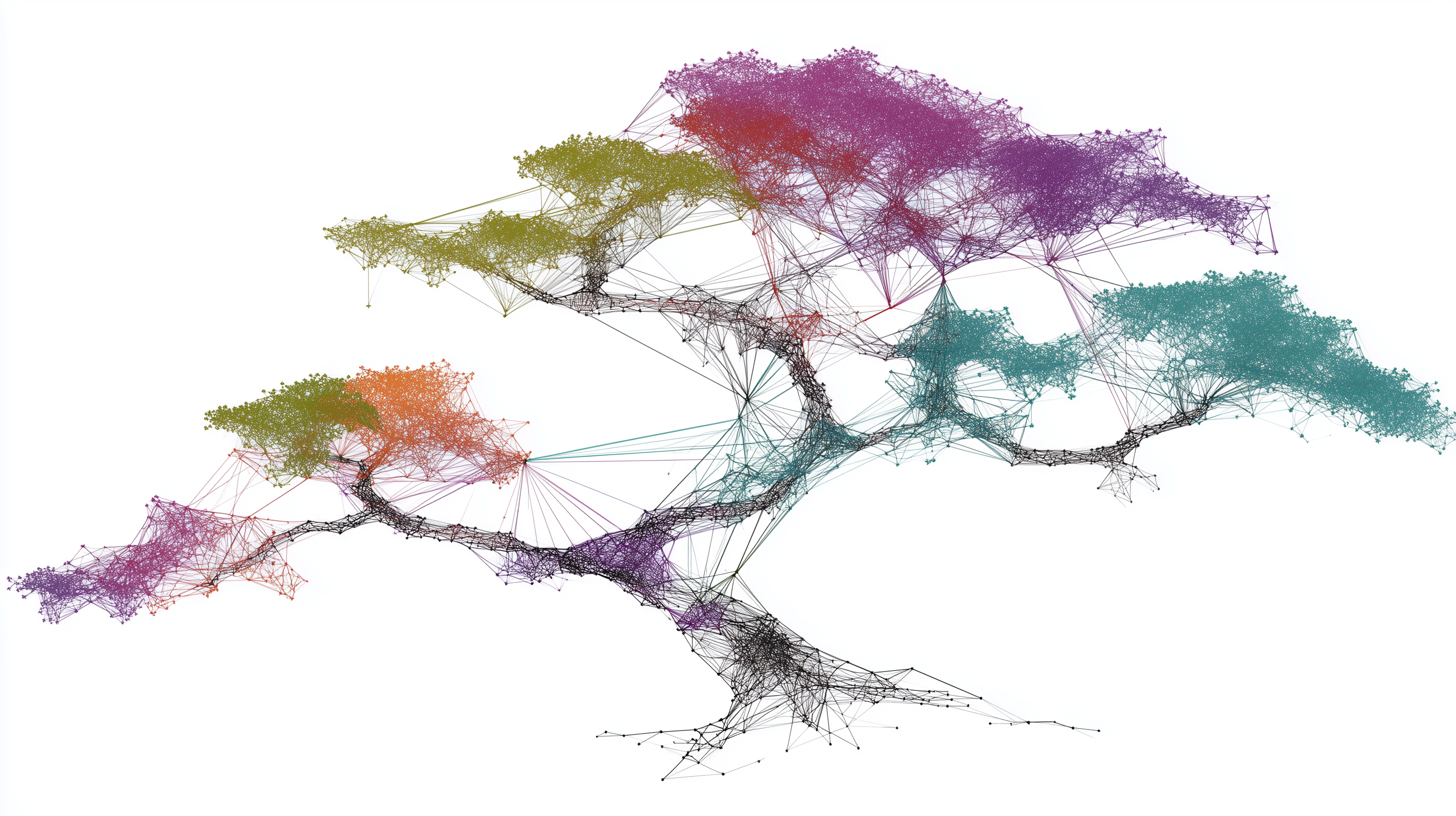

Software as bonsai

What if software engineering becomes more like gardening?

Written on

Tomorrow's software engineers won't write code, they'll grow it.

As AI systems become capable of autonomous development, our role as software engineers will shift from construction to cultivation. We’ll continually plant ideas, prune complexity, and shape living systems that evolve on their own, but under our watchful eye.

For the past few years, as part of Imbue, I've worked towards a vision of software and AI agents focused on individual human users--and their values1. We could see that increasingly powerful technologies would play a growing role in shaping our lives. Still, it wasn't clear how to operationalize that into something that increased individual agency and collective power over our systems and tools.

Then, one day about a year ago, I had a vision of the future of software creation.

In this future, people wake up, grab a cup of coffee, and check in on what has happened in their "software garden" overnight.

They make small adjustments--less of this, more of that, let's try something new over here--and then get on with their day.

In this new world, software is grown, not constructed.

In contrast, most software today is constructed by professional software engineers. While it's technically possible for software to do anything someone can imagine, any dreamer must rely on a software developer to turn that idea into reality. This leads to dynamics where software must serve a huge customer base to be worth building, forcing software applications towards the lowest common denominator. Software is built and sold to you; it's not grown, and users are at the whims of software creators to listen to their feedback or fix bugs.

AI coding agents let us flip that flawed paradigm on its head: now, everyone can create software. This creation becomes much more iterative, more personal, and tailored to the individual.

When you want a new piece of software, you provide the "seed" of the idea by telling an AI coding system what you want, and it... unfurls.

It starts by rolling out the idea. For example, let's say you're sick of seeing rage-bait in your news feed, and you want a program that will automatically filter it out. The AI coding agent can start working through the resulting questions:

- What are the implications of this idea?

- What are the primary challenges?

- How should the system be architected?

Next, the agent starts creating specs and design documents, iterating on them, and developing an implementation plan. Finally, it begins writing code--just little prototypes,scripts and experiments at first, to learn and test the boundaries of the idea. As it gains confidence, it gains speed. It begins fleshing out the system, adding tests, etc., and rapidly growing and flowering into the full application that you originally developed. This happens without any real effort on your part, beyond providing the goal and your preferences and values. In just a short time, you have a whole new way of interacting with the news, free from toxic content.

Eventually, these AI coding agents can even coordinate the deployment of the software they create, making your new idea available to your friends or even the entire world. Your great ideas can now effortlessly bloom into software that, overnight, changes how the world interacts with their computers.

It doesn't stop there.

Our future AI coding systems will understand (and fix) production errors. They'll watch for GitHub issues reported by other users on the open-source repository, and even respond to and potentially fix them. They'll answer questions in the community Discord in real time or teach others how to use your new software. They might even do marketing activities--spreading the word about this new software, gathering feedback, and gaining inspiration for new features you might want to add.

Software written in this way is more alive and organic than today's software. It expands and evolves and reacts to its environment--perhaps adapting to the changing landscape of software by specializing in a niche, adapting to users' changing needs, or expanding its scope to increase the number of happy users.

Like the growth of any living thing, this process takes time and energy. But unlike software development today, this will be primarily electrical energy for computing rather than mental energy from humans.

In such a world, our role as software creators will not be as engineers, responsible for the low-level technical details. It may be more like that of a "gardener"--setting the right preconditions and tending to the projects via similar activities like:

- "pruning" (removing dead or overly-complicated code, needless functionality, etc.)

- "transplanting" (copying in common code from one project to another so it can co-evolve, combining multiple projects to achieve a larger purpose, etc.)

- "harvesting" (publishing a successful prototype, actually using some "home-grown" scripts, etc.)

- etc.

Or perhaps we may become more like "software bonsai artists." Bonsai is a skilled and ancient tradition of shaping growth to achieve specific aesthetic and practical ideals. Much like traditional bonsai artists, we may develop techniques that shape our software into something pleasing to us, both individually, and as a society.

Rather than creating heaps of new slopware, we could adapt software to our own personal preferences, workflows, and tastes by carefully pruning and guiding the growth of those systems, rather than abdicating responsibility and allowing them to grow into a messy tangle of branches and thorns. By approaching it like bonsai, and ensuring the proper growth of technology that embodies our values, we could create software that is more secure, more respectful of personal privacy, and more humane.

This world is within our grasp.

Our AI software engineering systems are improving at an incredible rate. Sure, today’s systems like OpenAI's Codex, Claude Code, or Sculptor are perhaps best thought of as having a horde of mediocre interns at your fingertips. But these interns are improving at an incredible rate--far faster than I've ever seen most human interns improve, and we've had some pretty amazing interns. If this rate of improvement continues (or even fails to slow significantly), we will probably have systems capable of creating and deploying software in a fully autonomous way.

We're already seeing glimmers of these changes.

Claude Code has grown to over $1 billion in annualized revenue within 6 months, and has entirely rearchitected how engineering teams work. There is an obvious path towards a world in which engineers are no longer involved in typing out lines of code, and this has taken less than a year.

Or look at Cursor's latest experiment in having a team of AI agents create a browser (one of the most sophisticated pieces of the modern software stack) from scratch in just a few weeks. Sure, the code is probably garbage and it barely runs, but the fact that it works at all, and that this was orchestrated by a single human engineer (without ever writing any code by hand) is a testament both to the technical possibility of this idea, and the need for approaching the creation with this new "bonsai" mindset. It's no longer hard to get AI systems to produce lots of running code--the challenge is now constraining that code to be something beautiful.

There are other challenges to overcome before everyone is fully empowered to become software gardeners and software bonsai artists. There are payment rails to consider, deployment infrastructure to create, and even whole new UI/UX patterns to explore.

But the wonderful and crazy thing about open source software is that it only takes one person solving each of those problems once for the solution to become freely available to everyone.

This will likely happen within the next two years, and when it does, we will see an explosion of personal software.

Instead of using Spotify, we may grow music listening software that contributes directly to artists. Instead of browsing Goodreads anonymously to find our next book, we could create software that helps us organize a book club with our friends. Instead of simply reading news online, we can make software that annotates misleading and biased claims, automatically cites trustworthy sources, and helps us develop more accurate beliefs about the world.

It's only a matter of time before these capabilities get good enough that, at least for some of us, it's more fulfilling to "grow" software than it is to "construct" it. There is a beauty and joy that comes from interacting with more complex, "living" systems that feel very different from the cold, calculating, logical world of today's software.

When that happens, we may find ourselves not choosing between engineering and agriculture, but discovering they were never truly separate. The gardener who understands a soil's chemistry is as rigorous as an architect with blueprints. The future belongs to those who plant seeds with intention, and then tend them with care.

I, for one, look forward to visiting our future software arboretums and conservatories.

Footnotes

- We named the company Imbue because we want to help people imbue their values into their technology. ↩︎